We are going to be living in “Christchurch Central” for the next few weeks – as opposed to “Christchurch actual”. The two parts of the city seem to be completely cut off from each other. I have already been here for 10 days, but only have a vague idea of how this town works, or doesn’t work. I have to admit that during our first weekend here we were totally confused. Christchurch Central is one of the strangest cities I have ever seen – and that includes Longyearbyen (on the island of Spitsbergen), Jerusalem and even Bayreuth.

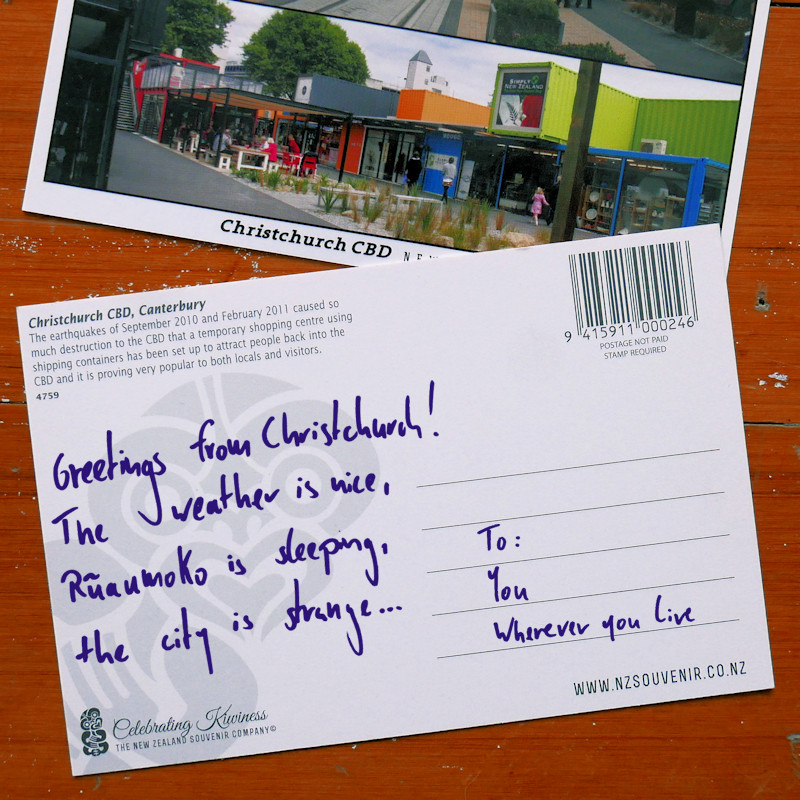

(Slideshow with analog Photos I have taken in Christchurch Central, klick on the picture for the next one!)

The inner city is a strange landscape of vacant lots, glass-walled office buildings only half-let, and fenced-in old buildings (most of which could collapse at any time, and are waiting to be demolished). It’s a weird mix of construction site and street art gallery, a place where no-one lives, with more or less equal numbers of tourists and construction workers, and the southern hemisphere’s biggest playground. At least for a time, it offers artists a space for experiments, and urban planners a laboratory for their radical, artificial, business-driven design concepts. This was once a city, that intends to be one again – a city that wants to get everything right this time around, yet is getting an awful lot wrong, with “visions” that fail to take account of the human factor.

(Click here or on the picture for my series of postcards from Christchurch!)

Up until 2011 Christchurch Central was apparently a “normal” inner city district, such as you would see in any western country– that’s what people tell me, and there are plenty of photographs to prove it. Workers, residents and tourists rubbed shoulders together here like anywhere else, and all the same problems were here as well: gentrification, long-standing local residents forced out by rising prices, and ever-increasing noise. Following the earthquake in January 2011, all that changed. For months the inner city was completely off limits, and only a fraction of the buildings remained (in most cases not completely destroyed, but so badly damaged that they have had to be taken down, floor by floor; some are still waiting in the “demolition queue”). The “rebuild”, as they call it, is more like a total reinvention, emerging from rubble, cleaned-up surviving structures and unreal looking open spaces.

And in the middle of all this – us, my girlfriend, our daughter and me, the only people living here, within a 500 m radius.