„The world is your oyster“, Ema says, but with a smile, because she doesn’t really mean it, and certainly not as any kind of criticism.

She is an artist and curator from Auckland, but of Fijian origin. We first met in Christchurch, when she was curating an exhibition in the Physics Room gallery.

But right now we are sitting in a cafe in Auckland, enjoying Samoan coffee and Tongan pie – unless it’s the other way around, anyway it’s delicious – washed down, bizarrely enough, with a Portuguese chocolate drink, also delicious.

(Ema Tavola – von der ich leider kein brauchbares selbstgemachtes Foto habe. Ihre Website ist definitiv einen Besuch wert: https://pimpiknows.com/)

Auckland is a very different city from the flattened pancake on the east coast of the South Island that goes by the name of Christchurch, with its wide open spaces, whiter-than-white residents, its obstinate refusal to be a real city, the gaping holes left behind by the earthquake, and its smattering of lifeless rebuilt shopping malls and office buildings.

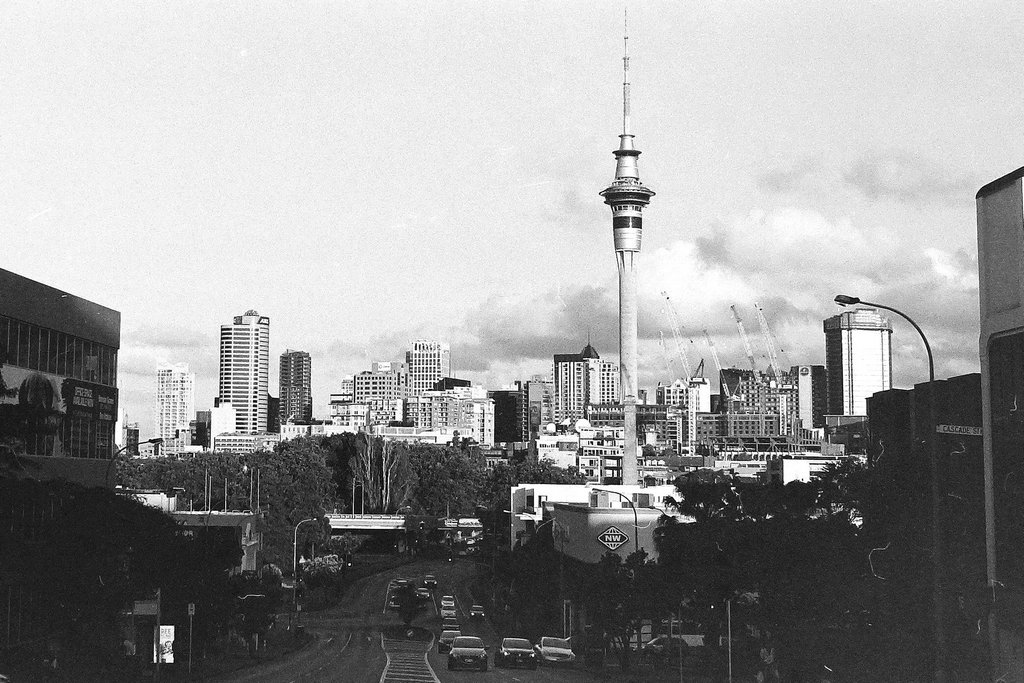

Auckland is built on hills, has a CBD replete with high-rise buildings and a TV tower, giving it a cool, metropolis-like look. It is loud, in your face and bursting at the seams, with a different climate, different vegetation, different everything, except for the same currency and supermarket chains. The people come in all shapes, colours and credit ratings. One moment you are gazing enviously at the rich and privileged types strutting around the marina, the next you are tossing a coin into the hat on the footpath beside a beggar, reminding you that you are not too badly off yourself.

The day before, Ema has taken us on a tour of South Auckland, home to large numbers of Pacific Islanders, immigrants from Tonga, Samoa, Fiji and other islands in the South Pacific.

I am learning a lot about their culture, their strong bonds with their island homes, their defiant pride in their origins, and also about the Maori, who also arrived here as immigrants from the South Pacific hundreds of years ago, long before the Dutch explorer Abel Tasman rechristened Aoteaora as „New Zealand“. Ema also tells me about racism, past wounds and ongoing discrimination. We discuss the situation of women in New Zealand, and everywhere, with a long and detailed digression on the topic of „mothers“. She also describes the difficult balancing act between holding true to her Pacific Island culture and overcoming its patriarchal, outmoded aspects.

Earlier this morning she went for a swim, she tells me, and in the changing room she found herself unwittingly eavesdropping on the conversation of three teenage Fijian girls, who clearly felt nothing but shame and disgust for their bodies. They were growing up with western films, western pop stars and the western ideal of feminine beauty, she said, bombarded with images of super-slim women with ultra-white skins. Yet they would never be white or pale-skinned themselves. The physique of Pacific men and women was quite different from that of Europeans, Ema tells me, and the stereotypical ideal figure with narrowly defined tolerances is an ideal that in most cases is completely beyond their reach (as it is for most European women, come to that). Many Pasifika women are beautiful and most are very striking in appearance but no atter how good they look: they do not fit the standard pattern.

The western ideal of beauty, or rather the unconditional and omnipresent nature of its representation, has disastrous consequences for European girls and women as well. It also has the effect of devaluing and debasing women, defining their bodies as their most important attribute, the basis of their sense of self-worth.

For white women the message is that they as individuals are ugly, that they don’t have a good figure, that they need to watch their weight, etc. Black women are generally excluded altogether. That’s the racist part of the story. There are one or two black film stars or models, like cocktail cherries on a mountain of white whipped cream (note to self: it may be time to change the metaphor-generator down a gear or two!). In New Zealand, as everywhere in the world, the cover of „Cosmopolitan“ magazine inevitably displays the sexy smile of a pale-skinned blonde.

(Slideshow with analog photos from Auckland andPiha Beach)

For the three girls Ema was telling me about, a sense of pride in their own origins and uniqueness would have been the best protection against their shame about failing to live up to the ideal presented by western magazines.

„I think it comes from being a minority“, Ema says, as we are taking about pride. „It’s a form of resisting being invisible. It’s a sort of survival strategy.“

She tells me about the art industry, where Pacific art admittedly does have a niche, but mainly as something exotic, for ornament rather than identification, sought out by western exhibition organisers to be displayed in spaces created for modern western art.

At one stage in our conversation I find myself talking about my own issues – my precarious situation as a freelance author, perhaps, or my troubles as the father of a one-year-old daughter, or how expensive beer is in New Zealand. But fortunately, just in time I realise that I should be the listener rather than the talker here, and interrupt myself: „Well, at least I’m white and I’m a man, I shouldn’t complain!“

Ema nods: „The world is your oyster!“ I was on the point of retorting that I didn’t like oysters (even though I had never eaten one) and that I couldn’t afford them, and that if I did I would be bound to break my teeth on a pearl. But Ema was smiling, because she didn’t really mean it, certainly not as any kind of criticism, and in a way she was quite right. So I just laugh with her, and keep my metaphor to myself. Instead of slurping down an oyster, I order another Portuguese chocolate.

(Thank you very much, Ema, for your time, your kindness and all your stories! I hope to see you again, someday, somewhere …)